“It was cruel and cold and brutal and beautiful, and I would give anything to go back there. Maybe it broke me in some deep, intrinsic way that I am incapable of seeing….I don’t care. It was my home, and it finally let me be myself, and I hate it here.”

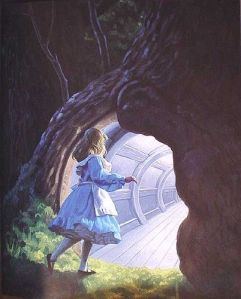

What happens to the Girl Underground after her adventure is over? Well, in a few glorious examples, she stays underground, but most of the time she ends up back in the “real world” either voluntarily (so many of them want so desperately to get home to their dull Kansas-like lands!) or as the natural conclusion to her journey. But what about those girls who never wanted to leave, and pine away for the magical world they left behind?

In Every Heart a Doorway, author Seanan McGuire introduces us to a boarding school made just for those girls (and a few boys) who stepped through a looking glass or went down an impossibly stairway inside a trunk, and ended up in a world they felt was truly “home” – only to get cast out again and be labeled “troubled” or even “insane” by confused parents.

Why mostly girls?

“Because ‘boys will be boys’ is a self-fulfilling prophecy…They’re too loud, on the whole, to be easily misplaced or overlooked; when they disappear from the home, parents send search parties to dredge them out of swamps and drag them away from frog ponds. It’s not innate. It’s learned. But it protects them from the doors, keeps them safe at home. Call it irony, if you like, but we spend so much time waiting for our boys to stray that they never have the opportunity. We notice the silence of men. We depend upon the silence of women.”

I don’t know that this is the full, true answer, but it may at least be part of it. Even more accurate, though, in my opinion, is her description of why the doors opened for these girls in the first place – and always into worlds that spoke to some deep, hidden part of themselves.

“Some doors really do appear only once, the consequence of some strange convergence that we can’t predict or re-create. They’re drawn by need and by sympathy. Not the emotion – the resonance of one thing to another. There’s a reason you were all pulled into worlds that suited you so well.”

She also speaks to how the journey changes a person. Those of us who understand the Power of Story and implement it in our lives will find this very familiar:

“The habit of narration, of crafting something miraculous out of the commonplace, was hard to break. Narration came naturally after a time spent in the company of talking scarecrows or disappearing cats; it was, in its own way, a method of keeping oneself grounded, connected to the thin thread of continuity that ran through all lives, no matter how strange they might become. Narrate the impossible things, turn them into a story, and they could be controlled.”

But no matter what they do, most of these girls won’t find their way back through their doors. Most Girls Underground return home and stay home, in the end. And for those who don’t want to, it must be excruciating. Especially as their memories and surety fade over time.

“My window is closing….Every day I wake up a little more linear, a little less lost, and one day I’ll be one of the women who says ‘I had the most charming dream,’ and I’ll mean it. [I’m] old enough to know what I’m losing in the process of being found.”

Every Heart a Doorway isn’t quite a Girls Underground story itself, but it cuts to the heart of this archetype in certain ways I’ve never seen before, and holds a lot of truth.

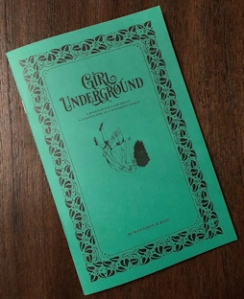

I mention this in the guidebook for the

I mention this in the guidebook for the

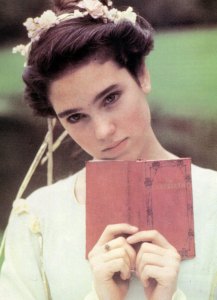

As long-time readers will know, this whole Girls Underground idea started with the movie Labyrinth – my favorite movie of all time, which I’ve seen hundreds of times. As I was watching it again recently, it occurred to me to write down some of the lessons from the Story, ones that are actually quite applicable to many spiritual and magical journeys. (Note: these were one of the inspirations for the Lessons cards in the

As long-time readers will know, this whole Girls Underground idea started with the movie Labyrinth – my favorite movie of all time, which I’ve seen hundreds of times. As I was watching it again recently, it occurred to me to write down some of the lessons from the Story, ones that are actually quite applicable to many spiritual and magical journeys. (Note: these were one of the inspirations for the Lessons cards in the